This essay originally appeared six years ago on Telesur English as a review of Gerald Horne’s important book The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America (New York, 2014). I offer it for re-publication and hopefully wider readership in the wake of the great 2020 George Floyd uprising, which has sparked a remarkable revisiting of the United States’ all-too living racist history.

How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?

– Samuel Johnson, 1775

“The Moral Equal of Our Founding Fathers”

On March 8, 1985, the right-wing United States President Ronald Reagan spoke in glowing historical terms about the Contras, the murderous counter-revolutionary force funded, trained, and equipped by the US to overthrow the popular Sandinista revolution and government in Nicaragua. “They are our brothers, these freedom-fighters,” Reagan told the Conservative Political Action Conference, “and we owe them our help. They are the moral equal of our Founding Fathers,” Reagan added, “and the brave men and women of the French Resistance.”

Reagan’s comments irked liberal and left-liberal US opponents of Reagan’s Central American policy. That policy involved the US providing training and funneling money, weapons, and other supplies to right-wing death squads across the region. The death toll was staggering: more than 70,000 political killings in El Salvador, more than 100,000 in Guatemala, and more than 30,000 murdered in the US proxy “contra war” on Nicaragua.

“He Has Excited Domestic Insurrection Among Us”

It was absurd, of course, for Reagan to identify the Third World-fascist Contras with the anti-fascist French resistance. But what most rankled many US liberals and progressives was the belief that Reagan had badly maligned the United States’ purportedly noble Founders by associating them with reactionary terrorists doing the CIA and White House’s illegal and dirty work in Central America.

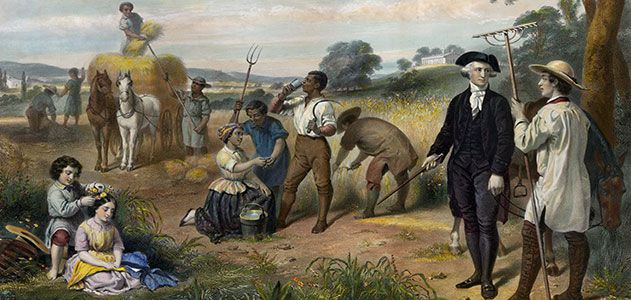

This liberal/left indignation was historically naïve. Reagan was (unwittingly) on to something when he linked the bloody and noxious Contras to the rich and powerful white North Americans (the “Founding Fathers”) who led the early US republic’s break-off from Britain. Forget for a moment that popular democracy even for whites was the Founders’ worst nightmare and that they crafted a government designed to make sure that the common people, those with little or no property, could not exercise any real power (for details, see Paul Street, “Democracy Incapacitated,” Z Magazine, July/August 2014, 28-30). Recalling that slavery was the main source of capital accumulation and proto-national wealth in late colonial British North America, look at this curious, rarely noted line in the Declaration of Independence’s (DOI’s) list of grievances against King George: “He has excited domestic insurrections amongst us, and has endeavored to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages, whose known rule of warfare, is an undistinguished destruction of all ages, sexes, and conditions.” Here the “royal brute” was accused of advancing social upheaval from the bottom up (“domestic insurrection”) in the New World – an instructive complaint, symptomatic of the “American Revolution’s” counter-revolutionary nature.

Rebellious Slaves and the Balance of Terror

The reference to North America’s indigenous people as pitiless barbarians who slaughtered without distinction was vicious slander. More than misrepresenting Indian culture and warfare, it anticipated Orwell by projecting onto Native Americans the genocidal practices the white North American settlers repeatedly used against the indigenes they ruthlessly murdered again and again

But go deeper. The reactionary reality of the DOI emerges more clearly when you realize what many of the leading North American colonists hoped to do with the land they wanted to seize from Jefferson’s “merciless Indian savages.” As the prolific historian Gerald Horne suggests in his recent book The Counter-Revolution of 1776: Slave Resistance and the Origins of the United States of America (New York, 2014), the (seemingly minor) line in the DOI quoted above reflects a central, fundamentally counter-revolutionary motivation behind the fateful decision to break off from England: a sense that the slave system on which North American fortunes depended could not survive except through secession from the British Empire.

As Horne shows, the expansion of a largely slave-based colonial economy across the New World during the 17th and 18th centuries had caused a serious problem for England, Spain, and France. Slaves came to outnumber Europeans in the colonial world. Africans in the Americas took notice of their demographic preponderance and recurrently revolted against their masters, forcing Old World authorities to invest ever-rising resources in repression. The colonizers tried to lure and (mainly through impressment) force enough Europeans to the colonies to sustain a balance of racial power and terror that would suppress slave rebellion. They failed.

To make matters worse from the Europeans’ perspective, Africans in the New World were empowered by increasing rivalry between the colonial empires. Great conflicts in Europe developed between the colonizers: The War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and the Seven Years War (1756-1763). These wars became global affairs in which colonial holdings switched hands between the great powers. They could not be waged in the Caribbean and South America without giving weapons to Blacks, and Black soldiers had to be freed if they were going to bear arms in European wars.

By the mid-18th century, as intra-European warfare further eroded the profitability of colonial enterprises, the colonial powers were looking for ways to accommodate their Black populations. In the Caribbean, Blacks were incorporated into colonial regimes. European rivalry had given rise to a new class of free Blacks Africans eager and equipped to fight in well-ordered military units against slavery and its remnants wherever they could be found. Hard-line resident British planters in Barbados shut down their operations and moved to North America, where the white/black ratio was less threatening.

The Path to Slaveholder Secession

White North American slave-owners and northern merchants who profited from the lucrative slave economy owners were not pleased with these developments. They experienced numerous slave revolts even in their part of the British Empire. Examples included major Black rebellions in Manhattan (1712, 1741) and South Carolina (the Stono Uprising, a mass 1739 uprising that included the massacre of dozens of settlers) – only the best-known incidents. White North American colonists across the 18th century reported numerous incidents of slaves poisoning their masters, plotting insurrections, taking over ships, and setting fires. “Black insurrectionists” were commonly said to be in league with the hated imperial rivals France and Spain. Horne notes that “one historian has observed as early as the 1760s that ‘every white person in the eastern counties [of Virginia] knew of a free person that had been killed by a slave’ [and that]…‘individual whites had nightmares about waking up amid slaves or feeling the first spasms of a stomach contorted by poison’” (Horne, The Counter-Revolution of 1776, p. 237). Between 1756 and 1763, the white settlers of North America “endured a remarkable spate of slave plots driven by the flux brought by the Seven Years War” (Horne, 237).

The settlement of that war played a pivotal role putting the US colonist-Founders on the road to secession (“Independence”). After its victory over France – following a war in which “London made extensive use of armed Africans” in the New World (Horne, 187) – the British government decreed a limit to the colonists’ territorial expansion on the North American mainland. The royal Proclamation of 1763 conflicted with the colonists’ insatiable lust for fertile land to plant and harvest cash crops with Black slaves – land inhabited by Jefferson’s “merciless Indian Savages.” Had the settlers been forced to remain within England’s confines, they feared, Black population growth would generate a “Caribbean” situation in North America. Their dread of black rebellion was enhanced by the constant influx into North America of black slaves infected with the “Caribbean virus” (resistance) – this thanks to the liberalization and dramatic expansion of the global slave trade in the 18th century.

There followed two further great steps on the path to the North American slaveholders’ secession – to American Independence. In the famous June 1772 Somerset case (Somerset v Lewis of 1772, 98 ER 499), the British court ruled that chattel slavery violated English common law. The application of Somerset to the thirteen British colonies would have meant an end to the slave machine that fed the coffers of the Yankee mercantile elite and fueled the wealth of New England (see below) while it created a wealthy landed aristocracy in Virginia, the Carolinas, and Georgia. The British judge responsible for the decision (William Murray Mansfield) became a special target of white colonists’ denunciation over the next four years.

The next landmark came in November 1775, when Lord Dunmore, the royal Governor of Virginia, offered to liberate and arm North American slaves to squash the anti-colonial rebellion under way since the Tea Act of 1773. With this action, Dunmore “entered a pre-existing maelstrom of [colonial] insecurity about slavery and London’s intentions” (Horne, 222). Across the future US South in the spring of 1775, elite colonists were consumed with fears of a slave insurrection allied with the British, Spanish, and/or Native Americans. “Lord Dunmore’s proclamation effectively barred any possibility of rebel reconciliation with London” (Horne, 234) as the colonists “now confronted Africans armed by London” (Horne, 237).

The Somerset decision and Dunmore’s edict irrevocably joined London with Abolition in the minds of the white colonists. The latter provided the decisive white rallying point for what historian Thelma Wills Foote accurately called “a white settler revolt” and “the white American War for Independence” – fought in no small measure to preserve and expand black chattel slavery. Independence emerged from “the state of the mind of the rebels” who already by early 1775 “coming to believe that a London-African combine was mounting against them, leaving secession – a unilateral Declaration of Independence – as the only way out” (Horne, 227, emphasis added). Two months before Dunmore issued his proclamation, rebels in South Carolina hung and cremated a free black man, Thomas Jeremiah, for saying that if England sent troops to repress the colonists he would join with the British gendarmes. Over the objections of South Carolina’s royal colonial governor, Jeremiah was tried and found guilty of “exciting the Negroes to an insurrection” (Horne, 226). “Even before the Dunmore proclamation,” Horne shows, “colonists were up in arms in light of alleged attempts by the crown to incite the Africans against them.”

When Dunmore issued his edict, there was no turning back from white independence, leading Horne to properly describe Lord Dunmore with irony as a leading US “Founding Father.”

It is hardly surprising that North American slaves identified the cause of Freedom with London, not the rebels. Tens of thousands of those slaves and many free blacks naturally “joined the redcoats” (Horne, 246).

Exceptional White Triumph in North America

The colonists’ triumph over London “brought about the reassertion of slaveowner control over the enslaved black population in the new republic” (Foote, quoted in Horne, 244). The North American slave system tightened and expanded in subsequent years. The color line between white and black was drawn with harsher lines than ever before in the “land of liberty.” Horne reflects on immediate and long-term consequences that does not jibe very well (to say the least) with the dominant national sense (shared even by many left historians) of the American Revolution as a democratic, forward-leaning development:

“there is a disjuncture between the supposed progressive and avant-guard import of 1776 and the worsening of conditions of Africans and the indigenous that followed upon the triumph of the rebels. Moreover, despite the alleged revolutionary and progressive impulse of 1776, the victors went on from there to crush indigenous politics, then moved overseas to do something similar in Hawaii, Cuba, and the Philippines, then unleashed its counter-revolutionary force in 20th-century Guatemala, Vietnam, Laos, Cambodia, Indonesia, Angola, South Africa, Iran, Grenada, Nicaragua and other tortured sites too numerous to mention” (Horne, 248).

The white North American settlers’ counter-revolution was a great slavery success – at least until the Civil War, when another white secession and military necessity compelled Abraham Lincoln to follow in Lord Dunmore’s footsteps by liberating and arming black slaves.

The “American paradox” (U.S. historian Edmund Morgan’s term), whereby “the Age of Liberty” was also “the Age of Slavery,” was not limited to colonial North America and the United States. As the historian Greg Grandin reminds us, “the paradox can be applied to all of the Americas, North and South…What was true for Richmond [Virginia] was no less true for Buenos Aires and Lima – that what many meant by freedom was the freedom to buy and sell black people as property” (Greg Grandin, Empire of Necessity: Slavery, Freedom, and Deception in the New World, New York, 2014, emphasis added). But consider this: of the 10 to 16 million Africans who survived the brutal Middle Passage to the New World, two-thirds ended up in Brazil or the West Indies. But by 1860, approximately two thirds of all New World slaves lived in the US South. In the US alone among the new Western Hemisphere Republics of the 19th century, slavery flourished rather than faded – until its destruction in the Civil War.

Part of the explanation for that disjuncture is the natural reproduction of slaves under the “paternalist” regime of the US South. Another aspect is the remarkable expansion of cotton slavery across the US South in the first half of the 19th century, intimately related to the early industrial revolution in England and Europe. A final piece is the white settlers’/slaveholders’ Counter-Revolution of 1776. The break-off slayed the specter of British Abolition and opened vast new swaths of land for genocidal theft from the continent’s original inhabitants and the deployment of new slave cash-crop production armies.

Northern Investment in Slavery

It wasn’t just the slave-owners of the southern North American colonies and early U.S. who had a strong vested interest in the survival and expansion of slavery. “Freedom”-loving New England, in many ways the spiritual and ideological cradle of Independence, was thoroughly embroiled in the system of black bondage. As the historian Lorenzo Greene noted 46 years ago, slavery “formed the very basis of the economic life of New England; about it revolved, and on it, depended, most of her other industries.” Grandin elaborates on the New England economy at the end of the 18th century:

“The expansion of slave labor in the South and into the West was still years away, but slavery as it then existed in the southern states was already an important source of northern profit, as was the already exploding slave trade in the Caribbean and South America. Banks capitalized the slave trade and insurance companies underwrote it. Covering slave voyages helped start Rhode Island’s insurance industry, while in Connecticut some of the first policies written by Aetna were on slaves’ lives. In turn, profits made from loans and insurance policies were plowed into other northern businesses. Fathers who made ‘made their fortunes outfitting ships for distant voyages’ left their money to sons who ‘built factories, chartered banks, incorporated canal and railroad enterprises, invested in government securities, and speculated in new financial instruments’….The use of slave labor in the North was ending [by the late 1790s], but throughout New England there were merchant families and port towns – Salem, Newport, Providence, Portsmouth, and New London among them – that thrived on the [slave] trade. Many of the millions of gallons of rum distilled annually in Massachusetts and Rhode Island were used to obtain slaves, who were then brought to West Indies and traded for sugar and molasses, which were boiled to make more rum to be used to acquire more slaves. Other New Englanders benefited more indirectly, building the slave ships, weaving the ‘negro cloth’ and cobbling the shoes to dress slaves, or catching and salting the fish used to feed them in the southern states and Caribbean islands (Grandin, Empire of Necessity, 79-80)

“Our Revolution…Alarmed at One Common Danger”

Ronald Reagan is hardly the only US president to have been fond of wrapping his administration in the supposedly glorious legacy of the US Founders and their “American revolution.” Barack Obama’s first Inaugural Address asked Americans to remember how “In the year of America’s birth, in the coldest of months, a small band of patriots huddled by dying campfires on the shores of an icy river. The capital was abandoned. The enemy was advancing. The snow was stained with blood. At a moment when the outcome of our revolution was most in doubt, the father of our nation ordered these words be read to the people: ‘Let it be told to the future world … that in the depth of winter, when nothing but hope and virtue could survive…that the city and the country, alarmed at one common danger, came forth to meet [it].”

For this writer at least, it was disturbing to hear the nation’s first black president citing the white War for Independence as an example of how “we” Americans united against “one common danger.” The new republic’s snows and soils and forests and tobacco, rice, and cotton fields had long been stained with the blood and tears of Native Americans and black slaves. Many North American slaves, free blacks, and indigenous people found and acted on good reasons to favor the British over the colonists in the war between England and the rising new racist and settler-imperialist slave state. England, after all, had put some limits on the pace at which the North Americans could steal the land the ruin the lives of the nation’s original inhabitants and turn western frontiers into sites for the ruthless exploitation of enslaved blacks. The British promised freedom to slaves who turned against their masters during the imperial settlers’ war of national slavery liberation. Sadly, the fate and struggle of the early republic’s black and red victims foretold the future struggles of Asians, Latin Americans, and Middle Easterners caught on the wrong side of the United States’ “freedom”-loving guns, alliances, and doctrines as the “infant empire” grew to toxic and deadly maturity and lethal senility.