The Paul Street Report, 11.21.2022

It’s the worst time of the sports year for me – the time when too many eyes and radio talk shows are focused on the vicious, hyper-violent brain-crushing and body-maiming blood sport that is US American football. It’s also the moment when we are furthest out from spring training for the beautiful, pastoral, artisanal, and (mostly) peaceful game of baseball, which was tragically displaced by fascistic “brain mash” (as a former colleague of mine once described US football) as the nation’s top sport decades ago.

And so it is that I am consoling myself by reading two excellent baseballs books – historian Rob Ruck’s Raceball: How the Major Leagues Colonized the Black and Latino Game and journalist Luke Epplin’s Our Team: Four Men and the World Series that Changed Baseball, a riveting account of (among other things) the Negro League legend Satchel Paige’s first (partial) season in the major leagues.

Under the influence of these volumes, my mind has turned to the topic of race and baseball, a game I used to play with a racially mixed group of fellow grade-schoolers on the University of Chicago Laboratory School sandlot down on 59th and Dorchester.

A Reason to Visit Wrigley Field Back in the Day

When I was a kid growing up on the South Side of Chicago in the mid and late 1960s, all my baseball rooting interests were focused on the American League’s Chicago White Sox over at Comiskey Park at 35th and Shields – the ballpark with the exploding scoreboard down at the bottom of the Irish-American Bridgeport neighborhood and across from the 100% Black Robert Taylor Homes on the other side of the Dan Ryan Expressway.

We didn’t care about the sorry Chicago Cubs in home or neighborhood. The Cubs resided in a foreign and absurdly white country called the North Side. They hadn’t been good enough to envy or otherwise care about for decades. We had American League rivals to worry about a lot more than the “lovable losers” up in Wrigley Field.

Still, I was always happy to make occasional trips up to the dingy old “piss-bucket” at Clark and Addison. I wanted to tag along to Wrigley Field because I collected baseball cards, followed all the major league stars, and wanted to see and gate autographs from the best players in the beautiful game I loved. And by the middle and late 1960s, those players happened to be disproportionately Black and in the National League (NL), which had integrated further and faster than the American League after World War II.

The Black baseball greats one could see in person at Wrigley included Lou Brock and Bob Gibson of the St. Louis Cardinals, Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell of the Pittsburgh Pirates, Willie Mays and Willie McCovey of the San Francisco Giants, Maury Wills of the Los Angeles Dodgers, Hank Aaron and Rico Carty of the Milwaukee (and then Atlanta) Braves, and Richie Allen of the Philadelphia Phillies, not to mention Billy Williams, Ernie Banks, and Ferguson Jenkins on the Cubs.

Big League Blackout

It was the late golden age of baseball, sadly being surpassed as the nation’s favorite sport by the atavistic nightmare that is U.S. “football.” It was also a golden age of US-born Black baseball stardom and pf US-born Black players presence in and atop “the American pastime.” By the late 1970s, Blacks made up 27% of major league rosters. Their presence was higher among the majors’ elite performers since Black players had to be better than whites to make big league rosters. (Many a good Black player languished his whole career in the minor leagues while inferior white players graduated to the “big show.”)

Both golden ages are long over. Football regrettably took over the national sports top spot at some point in the 1970s. And a report issued by The Institute for Diversity and Ethics in Sport last Spring found that there is now a smaller percentage of African-US-American Major League Baseball (MLB) players than there’s been in three decades. US-born Blacks comprise just 7% of MLB rosters, down from 18% in 1991. Remarkably enough, there wasn’t a single US-born Black player on either of the two teams in the 2022 World Series, the Houston Astros and the Philadelphia Phillies. It was the first time this had happened since 1950.

“I don’t think that that’s something that baseball should really be proud of,” said the Astros’ US-born Black manager Dusty Baker. “It looks bad. It lets people know that it didn’t take a year or even a decade to get to this point…What hurts is that I don’t know how much hope that it gives some of the young African-American kids,” Baker added. “Because when I was their age, I had a bunch of guys, [Willie] Mays, [Hank] Aaron, Frank Robinson, Tommy Davis — my hero — Maury Wills, all these guys. We need to do something before we lose them.”

Black US Americans are no more evident in big league stands than they are on the diamonds these days. US-born Blacks are also strikingly missing in the nation’s youth and adult amateur leagues, its high school and college and minor league rosters.

Standard White Guy Answers

What happened? Ask your standard white male U.S. sports fan and the answers you’ll get will cluster around the following:

+1. “There’s still a lot of Black players in the major leagues. Have you ever heard of Tim Anderson and Aaron Judge? And what about all the Black players from Latin America?”

+2. “I don’t know and, besides, who cares? Why do you commie liberals have to bring race into everything?

+3. “Baseball isn’t the main national sport anymore: football is, and basketball may have surpassed it. And most of the NBA and NFL players are Black now. Black kids grow up wanting to be basketball and football players. They don’t want to play baseball anymore. Get over it.”

Answer number one simply dismisses the specifically US-born Black disappearance, as if the continued existence of a slight few members of a dying species invalidates their Endangered Species status.

I’ll get to the rising Latin presence near the end of this essay.

Besides falsely conflating liberalism with communism (as white guys who listen to talk radio often do), the second response reflects the nauseating fake color-blindness that masks racial disparity in all walks of US-American life. Any decent society would be concerned about one of its homegrown racial groups’ significantly declining presence in one of its major social and cultural spheres – a detriment to the sphere’s quality as well as to its “diversity.”

Answer number three touches on real developments but misses key parts of the story to be related in this essay’s next subsection. It also lacks proper sadness over a beautiful and arcadian game’s transcendence by a ferocious activity that wrecks bodies and minds while promoting and normalizing violent cruelty. US “football” chews players up and spits them out in remarkably short time for lower per-season and lifetime pay. Imagine if spectacular Black athletes like Hank Aaron, Barry Bonds, Lou Brock, Willie Mays, Michael Jordan, Julius Erving, Reggie Jackson, and Kobi Bryant had been sucked into the lethal orbit of US “football” instead of baseball and basketball in their youths. Many of them would very likely have suffered terrible injuries early in college or National Football League careers. Who knows how long before they’d have shown the debilitating mental and physical signs of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE)?

(The also beautiful game of basketball is not a step down from baseball in terms of health, aesthetics, and morality, but its roster spots are far more limited in a game that puts just ten players on a court at a time.)

“The Greatest Untapped Reservoir of Raw Material in the History of the Game”: Inter-Capitalist Competition and War Brought Blacks into the Onetime American Pastime

But let’s dig deeper into the historical-material substance of the question posed: what happened to US Black baseball? Like so much else that merits mourning in our modern world, you’ve got to examine the ongoing history of capitalism to get to the root of Black America’s rise and fall in baseball.

Dusty Baker is right that “it didn’t take a year or even a decade to get to this point.” Now he needs to investigate the developing (and under-developing) racial political economy of the game over the last century.

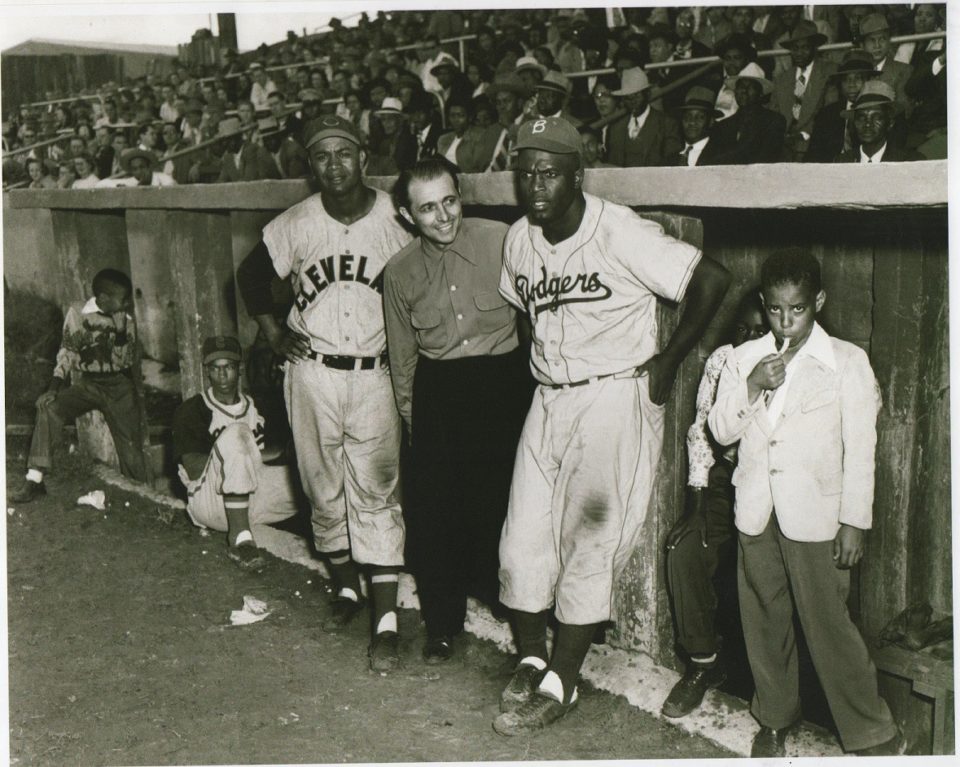

Black players came into the major leagues in 1947 after a half century of Jim Crow banning. The critical first steps were the playing that year of Jackie Robinson by the renegade Brooklyn Dodgers’ owner Branch Rickey and Larry Doby by Rickey’s American League counterpart Bill Veeck of the Cleveland Indians. Robinson and Doby’s successful first seasons opened the door to a Black major league influx that turned MLB into a great momentary symbol and agent of Black civil rights.

But what produced the end of Jim Crow in MLB? It wasn’t exactly a good-hearted spirit of inclusiveness on the part of Major League owners and authorities. As Epplin notes in Our Team:

“Rickey’s push for integration was…complicated…Personal experience and Christian principles had persuaded him of the injustice of the color line…But Rickey was not motivated solely by altruistic concerns. The potent Dodgers club he’d taken over late in 1942 carried scads of players on the wrong side of thirty. That season they’d faded in October, squandering the pennant to the youthful St. Louis Cardinals. Rickey, who’d assembled that same Cardinals roster, knew that if the Dodgers stood pat, the Cardinals would continue to lap them. One evening, while playing bridge with Harold Parrott, the team’s traveling secretary, Rickey made his purposes clear. ‘Son,’ he told Parrott, ‘the greatest untapped reservoir of raw material in the history of the game is the black race! The Negro will make us winners for years to come. And for that I will happily bear being a bleeding heart, and a do-gooder, and all that humanitarian rot.” (Epplin, Our Team, pp. 95-96, emphasis added).

Along with some owners’ relative immunity from the toxic anti-Black racism (especially true in Veeck’s case) that had long infected MLB’s ownership and commissioners’ office, the Black player infow was about capitalist owners’ competitive desire for wins, publicity, ticket sales, and radio and television contracts.

As Ruck shows in Raceball, the remarkable Negro League infrastructure that had grown up in response to the racial ban had long produced Black players capable of competing and indeed excelling at the Major League level. The best US-born Black players had long proven their mettle against the best white players both in Mexican and Caribbean winter leagues and during interracial barnstorming tours that stars like Dizzy Dean (white) and Paige held across the county (typically in places located far from major league cities) to pad their paychecks following the conclusion of the major and Negro league seasons.

In big US cities across the country, moreover, millions of white as well as Black fans had watched great Black players like Paige and Josh Gibson (“the Black Babe Ruth”) in Negro League games tcommonly played in the same ballparks used and owned by all-white Major League clubs. (Many Negro League teams had been a profit source for MLB franchises since they had to rent big league ballparks.)

It was probably just a matter of time until the color line was broached in the major leagues – something that Black newspapers and communist and other union and community organizers had been calling for since the 1930s – after World War II. Baseball integration was a popular civil rights issue across northern cities during and after the war. Hadn’t tens of thousands of Black soldiers just fought in the epic global struggle with the explicitly racist Nazi and Japanese regimes? How could Blacks be denied the right to show their talents at the highest level of the national pastime after putting their lives and bodies on the line in the great world war against fascism?

Integration as a Curse

But, as Ruck shows, the racial integration that followed the Robinson and Doby breakthroughs was a double-edged sword. Integration was both a national civil rights triumph and a practical curse for Black baseball. Most of the early Black Major League greats – this included Paige (the greatest pitcher of the century, who did not enter the majors until he was well into his forties), Mays, Aaron, Banks, and many others – had developed their skills within the impressive and largely Black-owned system of independent Black baseball.

The integration of the Major Leagues may have been a profound symbolic civil rights victory. But when the big leagues began to colorize their rosters and their minor league systems, they did so without heeding Negro League owners’ and advocates call to bring in some of the Black teams and /or incorporate the Negro Leagues into their minor leagues. MLB integrated in a way calculated to collapse the Negro Leagues, the critical developer of Black baseball talent, culture and fans.

Adding insult to injury, even a relatively non-racist MLB owner like Rickey took delight in raiding Negro League rosters without offering compensation to the teams from which he cherry-picked Black players like Don Newcombe, Roy Campanella, and John Wright.

Priced Out

Later developments sealed the fate of US-Black baseball. The rise of locally and nationally televised major league baseball shrank fan turnout and profits for local, semi-professional, industrial and other smaller league baseball teams, further undoing the social and institutional environment that had nurtured elite US-born Black players.

With the relative decline of the minor leagues, the majors increasingly drafted players out of college baseball. This was a steep barrier to entry for Black players whose families could not afford college tuition. NCAA schools offer few baseball scholarships compared to the largesse they spend on football and basketball recruits, something that has helped bias Black high school athletes toward basketball and football.

As youth and adolescent sports increasingly focused on the development of a single sport, baseball success increasingly required youthful participation in expensive private camps and programs beyond the financial reach of most Black families.

Baseball skill formation and facilities became investments beyond the resources of Black communities in hyper-segregated and deindustrialized communities of savagely racialized poverty. (The new American League home run king Aaron Judge, himself half-white, was adopted by white suburban middle-class parents who put him in proximity to and contact with the resources required for rising in baseball today.)

Along the way, only older Black Americans retain fond recollections of the great Black major leaguers of players of old (Mays, Aaron, Gibson et al) much less the Negro League greats like Paige, Gibson (who died the same year that Jackie Robinson and Larry Doby broke the MLB color line) and “Cool Papa” Bell. With all due respect for US-born Black 1970s-1990s baseball greats like Joe Morgan, Reggie Jackson, Andrew Dawson, Frank Thomas, Derek Jeter, and Ken Griffey, Jr., the new Black American sports legends since the 1960s-70s have been mainly boxers, “football” players, and above all basketball players. The demonization of the Black all-time major league home run king Barry Bonds (for using steroids and being a public relations nightmare) has hardly helped entice Black youth back into baseball.

Skyrocketing ticket costs – the days of sitting in a major league bleacher seat for $1.50 are long gone – don’t help bring Black fans back to the ballpark in a nation where median Black household wealth is equivalent to seven cents or less on the median white household dollar.

The Latin Ascendancy

See a Black player in the big leagues today and chances are he’s from Cuba, Puerto Rico or above all the Dominican Republic. The major leagues are now 32% Latino/Hispanic. MLB now employees more than 190 Latin players, up from just three in 1947.

How and why did that happen? Once again, it’s about the intersection of race and capitalism-imperialism. As Ruck shows, U.S. MLB defeated independent Mexican and Caribbean leagues in the competition for talent (including white talent) in the 1940s and 1950s. This and the fact that the rich baseball goldmine Cuba ended professional baseball on the island with its 1959-61 socialist revolution meant that great Latin players seeking to cash in on their skills had to go north to the US major leagues, just like great Brazilian, Argentinian, and Nigerian soccer players head to the British Premier League or its European counterparts to maximize their earnings.

Two other factors stand out. The Latin players have typically been one-sport athletes with little chance of competing for football or basketball scholarships. At same time, the big leagues have invested heavily in specialized “baseball academies” meant to develop talent from a young age across the Dominican Republic (DR). Talk about “tapping reservoirs of raw material in the history of the game” (Branch Rickey)! It’s a form of industrialized colonization for imperial export. Beginning in the mid-1980s, Ruck notes, “the academies mean that MLB had …systematize[d] player procurement and development while cultivating players at a fraction of the cost of securing comparable talent in the United States. Few major league investments have ever proved more efficient or productive”(emphasis added).

But MLB did not invent sterling Dominican and Cuban players like Albert Pujols, Pedro Martinez, Adrian Beltre, Vladimir Guerrero, Alex Rodriguez, Jose Abreu, Yuli Gurriel, Jorge Soler, and Luis Robert out of thin air. They exploited a rich pre-existing Caribbean baseball tradition that goes back to the early 20th Century. As Ruck shows, it is by no means clear that the best baseball in the world was played in the United States in the 1920s and 1930s. An equally advanced level of play was evident in the DR and Cuba during the inerwar years. In a short matter of decades, however, the best Latin American artisans of the diamond would come to understand that there was only one game in town when it comes to making a serious living at the game they loved: the North American major leagues.

Reflecting Fidel Castro’s love for baseball, moreover, Cuban “socialism” has continued to generate a steady stream of great players for MLB export.

…As Another Black Athlete Gets Chewed Up and Spat Out by Brainmash

But for these underlying developments rooted in capitalist-imperialist political economy, the White Sox cocky Black shortstop Tim Anderson – an American League batting champion from Alabama – might feel like less of a throwback to another era. Who’s to say that thousands of Black athletes who have seen their bodies and minds damaged by US football would not have preferred to develop their skills and play professionally in the beautiful game of baseball if given real opportunities to do so? Recall that the greatest basketball player of all time, Michael Jordan dreamed of being able to play baseball at a major league level, going so far as taking time to try to compete in the minor leagues (where he hit around .200) between his two championship runs on the Chicago Bulls.

Anyone looking for a fix from ownership is naïve. There isn’t a single majority Black owner in MLB. By the summer of 2020, there was only one majority Black owner in all of professional U.S. baseball. But then there’s only one majority Black owner – Jordan – even in the NBA, where 73% of the players are Black.

It’s hard to see the situation changing short of a major alteration in underlying trends. Still, it’s depressing to watch one Black athlete after another who ought to be working on his batting stance or his pitch repertoire in the off season being carried off the fascist gridiron with a crippling or suffering the consequences of a concussion caused by yet another hit in the new national pastime – “Brainmash.”

Postscript (12-16-2022):

If I had more space for this essay, I’d have included Epplin’s reporting on the white Iowa fireballer Bob Feller’s racially condescending comments on Satchel Paige (who Feller absurdly called “lazy” and unwilling to “bear down enough” in 1941) and Jackie Robinson — and on Black players more generally. Back from a brief stint in the Pacific War, Feller tells reporters this in 1946 : “I can’t see any chance at all for [Jackie] Robinson. And I’ll say this — if he were a white man, I doubt if they’d even consider him big league material” (Epplin, Our Team, p. 86). Wow — a white guy who was set up for baseball success by his baseball-obsessed father from grade school on voicing absurd notions of reverse discrimination with whites as the suposed victims (right) in 1946, before Robinson begins his very successful career in MLB. Quite a not-so subtle racist Feller was, whatever his willingness to barnstorm with Black players prior to MLB integration. I doubt this is featued in the Bob Feller Museum in Feller’s home town in Van Meter, Iowa, located in a now savagely right-wing “red” (brown) state. Paige by the way is brought up by the “Indians” (that racist team name and the wildly offensive logo that went with it are now finally and thankfully gone) in the middle of the 1948 season. He goes something like 6 and 1, pitching brilliantly and yet is the last pitcher the Cleveland team puts on the mound in the 1948 World Series. The Cleveland team wins the series thanks in no small part to Doby but the white phenom Feller loses both of his starts.